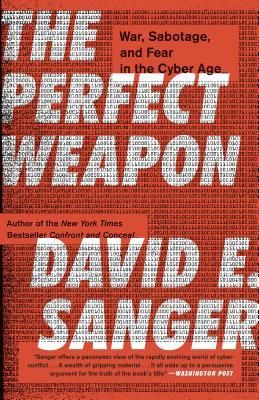

The passage continues: “ Ever resourceful, Mandia’s staff of former intelligence officers and cyber experts tried a different method of proving their case. Yet as long as none of his investigators could get inside the building, whether physically or virtually, to identify the thieves, the Chinese would keep denying that their military had been tasked with stealing technology for state-run Chinese firms. Over seven years, he had compiled a list of the unit’s suspected attacks on 141 companies across nearly two dozen industries, but he needed solid evidence before he could name them. In “The Perfect Weapon: War, Sabotage, and Fear in the Cyber Age,” New York Times national security correspondent David Sanger writes that the U.S.-based cybersecurity firm Mandiant penetrated a Chinese military cyber unit after it hacked into one of its customer’s systems in order to nail down attribution.Īccording to Sanger, while Mandiant observed Chinese hackers breaching a client several years ago, they used it as an opportunity to target the attackers’ systems, which allowed access to a video camera that exposed the hackers’ faces: was certain the hackers were part of Unit 61398, but he also knew that accusing the Chinese military directly would constitute a huge step for his company. The company that authored a watershed report on how Chinese hackers operate is pushing back against claims in a new book that the research was conducted through the use of illegal offensive hacking techniques.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)